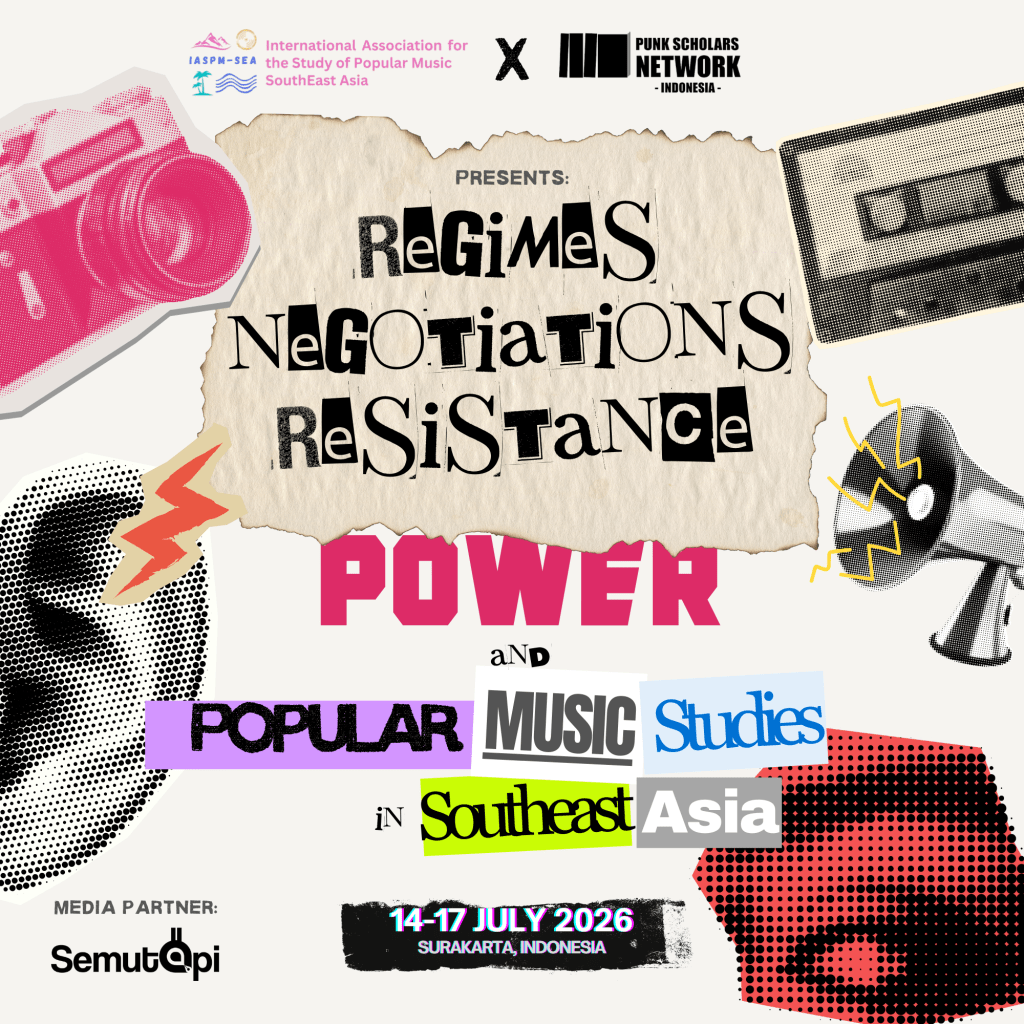

IASPM SEA x PSN Indonesia 2026 Conference

Popular music has been historically positioned and utilized to both reify as well as defy authority. Gen-Z popular culture dominated recent protest movements globally and across Southeast Asia both on and offline. In places such as Indonesia, Timor Leste, Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar, activists, students, protestors, and netizens mobilised cultural symbols and especially music to express discontent, decry injustice, and forge solidarities among geographically distant communities. At the same time, governments utilised their political powers to further their agenda through popular music, at times inadvertently but at other times, directly. Governments in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Myanmar mobilised their influence over mass media to overpower grassroots movements by dominating the airwaves with politically sanitised or nationalistic music in attempts to quell public discontent and resistance.

Popular music has also been instrumental in understanding and mediating issues of negotiation and resistance against technology. Resistance against mass-consumed digital streaming manifests strongly among younger generations who are instead turning toward analog media and technology such as vinyl records, cassettes, and recording devices to consume and produce music. However, this analog-digital divide is problematised by the growing popularity of “analog-modelling” digital technology like amp simulators and lo-fi effects used by artists and bands when performing and producing music.

Investigating dynamic relations of regimes and resistances in Southeast Asia through popular music also elucidate the crucial effects of colonialism in the development of cultural tastes and political struggles. Southeast Asian nations and peoples have neither fully accepted nor rejected the influences of colonialism but have always negotiated these post-independence. Until now, predominant styles and aesthetics in popular music are influenced by artists and trends in the Global North, and by extension, systems dictating the consumption and production of music are still informed by media frameworks that are inherited from and shaped by colonial structures of the past and dictated in the present by the corporations and cultural systems belonging to those colonial powers.

Looking retrospectively at these historical negotiations of power, popular musics today that echo historical narratives of resistance must re-examine its positionalities to earlier movements. As popular subgenres emerge, their practices, artists, and aesthetics epitomize images of resistances against established and older hegemonic values as a form of subcultural expression, illustrating what Stuart Hall (2006) describes as emergent cultural forms, resulting from interventive spaces and negotiations among these opposing forces and value systems. This dynamic relationship between “old” versus “young” fuels and reifies popular music as a vehicle for counter-hegemonic resistance as often exemplified but not limited to punk rock and its tense link to conservatism and authoritarianism. However, as the “young” become “old” and newer subcultures emerge, how does this change the musical and political landscape of resistance? How do younger generations within that subculture now make sense of its inherited narrative of resistance as figures and icons of subcultural resistance have aged, become established, and now represent the very groups they once opposed? How is the resistance of popular music subcultures interpreted now that its actors have entered circles of power?

Guiding Questions:

- How do popular cultures, musics, and soundscapes historically interact with political and economic realms, structures, and subjectivities in relation to Southeast Asia?

- How are popular music fans, artists, genres, and scenes affected by authoritarian regimes?

- Conversely, how are authoritarian regimes affected by popular music fans, artists, genres, and scenes?

- What other (non-nation-state) regimes might be considered in the context of studying popular music? e.g. regimes of genre, scenes, recording, and entertainment industries.

- How do alternative, non-mainstream, or underground music scenes represent expressions of everyday resistance or negotiation?

- What are the intergenerational continuities and life cycles of resistance that can be heard in certain genres of popular music like hip-hop, punk, and heavy metal?

- Similarly, what are the continuities and life cycles of oppression perpetuated by authoritarian/capitalist/neoliberal/postcolonial regimes on popular music fans, artists, practices, and scenes?

- How do fans, artists, and musicians negotiate their expressions in the context of their society, culture, community, generation, and nation-states?

Sub-themes of regimes, negotiations, resistances, and popular music in relation to:

- Intergenerational dynamics (e.g. Boomer, Millennial & Gen-Z dynamics, aging fans and artists)

- Technologies of music consumption, distribution, production, and aesthetics

- music learning, education and institutions (e.g. music certification, tertiary education, informal vs formal pedagogy)

- The clash and fusion of genres and emerging new scenes

- Gender and sexuality

- Race and ethnicity

- Tradition and culture

- Society, community, nation-states, and regional subjectivities and identities

We invite abstract submissions for multiple formats (listed below) for PSN Indonesia’s 7th and IASPM-SEA’s 6th International Conference.

Submission Instructions

All proposals are subject to peer review. Individual papers will consist of a 20-minute presentation followed by a 10-minute question and answer portion, while organised panels will be given a total of 90–120 minutes (3–4 papers) and 120–150 minutes (4–5 papers). We also welcome Performance lectures, poster presentations, and video screenings. Proposals should include full name(s), affiliation(s), and contact details for presenter(s), and an abstract of no more than 300 words. For organised panels, please submit an overarching panel abstract and individual abstracts.

The deadline for submission is Friday, 13 March, 2026. Please submit your abstract proposal to the link: https://forms.gle/wHHdwmpnE8BuATPfA

Authors will be notified of their acceptance in April 2026. A preliminary conference program and details on conference registration and accommodations will be released in May 2026. (The Local branch Executive Commitee will announce the conference fee in due time)For further inquiries, please contact iaspm.sea.conference@gmail.com.

Leave a comment